“And now we come to a turning-point in the career of Santa Claus, and it is my duty to relate the most remarkable circumstance that has happened since the world began or mankind was created.”

Histories of Christmas are pretty much endlessly interesting to me. I love piecing together Sinter Klaas, St. Nicholas, Wotan, Three Kings’ Day, Saturnalia, and the Nativity. I love the Krampus. I love Mari Lwyd and Jólakötturinn and the Jólabókaflóð and the Yule Log. Most of all maybe I love Christmas specials, and of all Christmas specials I love those of Rankin/Bass the most. Their decades-long project was to create a single unified theory of Christmas—a Christmas Cinematic Universe, if you will—which included everyone from Rudolph and Frosty to the Little Drummer Boy, and even a few leprechauns for good measure. But best of all were the multiple Santa Claus origin stories, including one particularly bizarre tale.

The Life and Adventure of Santa Claus became one of those weird half-memories where I wasn’t entirely sure whether I’d dreamed it. Had I really seen a special where Santa was suckled by a lioness? Where a group of fairies went to war with a group of demons to get Santa’s toys back? Where everyone joined in and sang a dirge about immortality as they debated whether or not Santa should die?

For years I wasn’t sure whether I’d dreamed it—or what that meant about me if I had.

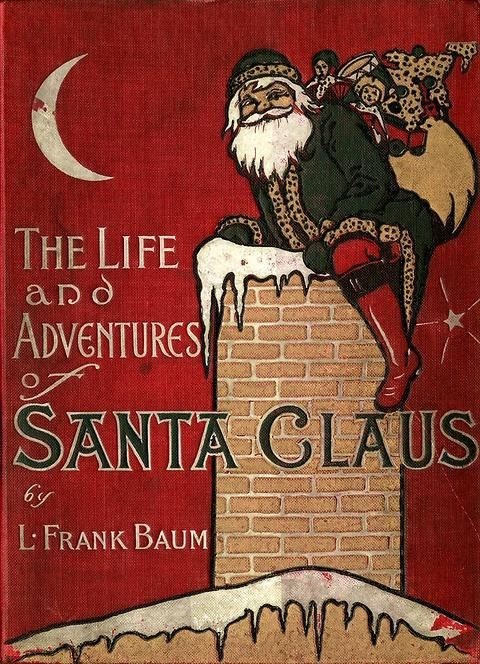

But then finally I found it again during a Christmas special marathon, and it was just as weird as I remembered, and even better, it was based on a book! L. Frank Baum, the mighty creator or Oz, wrote a Santa backstory in 1902 that fills in some of the gaps of his story, and it’s really fascinating to see what bits have lasted, and which haven’t.

Buy the Book

Life and Adventures of Santa Claus

I’ll need to delve into a little Christmas history before I talk about the book, so bear with me! Originally classy Protestants visited each other and exchanged gifts on New Year’s Day, with Christmas seen as a more boisterous Catholic holiday. The New Year’s Eve or Day services were solemn, with an emphasis on taking stock of a year as it ends, or squaring your shoulders as you march into the coming year. A few early Christmas-themed works helped finesse the holiday into a celebration of children, filled with toys and treats as reward for good behavior all year.

In 1809, Washington Irving’s 1809 Knickerbocker’s History of New York featured a St. Nicholas who rode through the sky in a wagon and smoked a pipe, but offered no explanation of his magical powers.

In 1821 “Old Santeclaus with Much Delight” was published by William B. Gilley in a paper booklet titled The Children’s Friend: A New-Year’s Present, to the Little Ones from Five to Twelve. The poem, which you can read here, explicitly sets Santa’s visit as Christmas Eve (though the book itself is called a “New-Year’s” present), seems to be aimed primarily at boys, and sets Santa up as moral judge, with a harsh warning that switches will be left for disobedient children.

Finally Clement C. Moore’s 1823 “A Visit from St. Nicholas” makes Santa an explicitly friendly figure: “a right jolly old elf.” The poem, like Irving’s tale, simply reports the visitation, but Nicholas’ backstory and magical abilities remain a mystery. He has a red fur suit, a round belly, a cherry nose, and a pipe. He puts his gifts into the children’s stockings, which have been hung up for him specifically, and he travels back up the chimney by placing his finger beside his nose, as in Irving’s telling. Instead of a “wagon” he has a tiny sleigh and “eight tiny reindeer” originally listed as Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder, and Blixem” retaining the Dutch spelling of the last two names. These were later changed to the Germanic “Donder and Blitzen” by the 1840s, and further evolved into Donner and Blitzen by the 1900s.

(Rudolph wasn’t added until 1939, when Montgomery Ward department store published a story about the Red-Nosed Reindeer written by Robert L. May, and distributed as a promotional coloring book. A mass-market version of the book came out in 1947.)

In the 1860s Thomas Nast did a series of Santa Claus illustrations that helped set him in the public’s mind as a peddler with a bag of toys, and in the later 1860s George P. Webster’s poem “Santa Claus and His Works” posited that the right jolly old elf lived near the North Pole. By the end of the 19th Century, Santa was firmly enshrined in American popular culture, to the extent that The New York Sun’s “Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus” editorial could become an instant classic, rather than inspiring a nation of people from a variety of backgrounds to ask who the heck Santa Claus was, as would have happened even two decades earlier.

At which point we join L. Frank Baum and his Santa Claus origin story.

Baum goes full pagan with his story, and essentially retcons a lot of the existing mythology to give everything a fantastical origin. Santa walks the line between human and “jolly old elf” by being a human baby who was adopted by the Wood Nymphs of the Forest of Burzee. The Wood Nymphs are but one branch of a family of Immortals who include Nooks (the masters of wildlife), Ryls (the masters of flora), Fairies (the guardians of mankind) and, most impressively, The Great Ak, the Master Woodsman who guards all the forests of the world. Raised by these creatures, young Claus grows up without fear of man or beast, with love and reverence for nature. He’s also, as I mentioned above, nursed by a freaking lioness. He decides to become a toymaker to bring joy to children, and lives alone in a cabin in the Laughing Valley of Hohaho, a liminal space between the fully magical Forest of Burzee and the harsh world of humans. Once he begins making toys, Baum throws himself into different parts of the Santa Claus mythos.

Santa visits on Christmas Eve because that’s the one night the Nooks will allow him to borrow reindeer. There are ten reindeer, not eight, and their names are Glossie, Flossie, Racer, Pacer, Reckless, Speckless, Fearless, Peerless, Ready, and Steady. Santa comes down the chimney because the first time he ever tried to deliver toys at night he found a town full of locked doors, and had to find an alternate means of entry. The stocking thing began as an accident before evolving into a way for empathetic parents to make his job easier – dropping toys into the stocking allowed him to zip right back up the chimney. He climbs up and down the chimney rather than magicking himself around. And maybe most important, at no point does he leave coal or switches or even peeved notes for the children. He loves all children. He believes that “in all this world there is nothing so beautiful as a happy child,” and so he wants to make all of them happy so they can be more beautiful.

Yes, there is a battle between the good Immortals and the nasty “Awgwahs,” but Baum doesn’t waste much time on them. He understands that for a child reading the book, the big conflict is baked right in: how were toys invented? Why did Christmas become the night when toys were delivered? Can anything hurt Santa? And he answers these questions in simple, logical ways, without resorting to over the top drama. Children are sick and neglected. People struggle to keep food on the table, and have no time left over to play with their children, or whittle toys for them. So Claus dedicates himself to doing a thing that many find frivolous, and is soon hailed the world over as a saint. Which brings us to the one note of true drama in the story, and the line I quoted above: the Immortals must decide whether to bestow the Mantle of Immortality upon Claus, so he might deliver toys to children forever.

I won’t spoil the ending, but you can probably guess.

Baum wrote two short story sequels to the book, both of which were published in 1904. One, titled “”How The Woggle-Bug And His Friends Visited Santa Claus,” appeared in his newspaper series, Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz. It makes it clear that this is all one big universe, because Oz’s own Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman drop in on Santa Claus to donate some toys they’ve made. A more direct sequel, “A Kidnapped Santa Claus,” appeared in The Delineator magazine. As one might expect from the title, Claus is kidnapped—by Daemons—and his assistants have to deliver the toys in his stead. (Don’t worry, Santa Claus gets away just fine.) Five years later Claus is a guest a Princess Ozma’s birthday party in The Road to Oz, and he returns to the Laughing Valley of Hohaho via giant soap bubbles, as one does.

The most striking thing to me is the absolute absence of Christian symbolism in this origin story. In most of the other early versions St. Nicholas is, well, St. Nicholas. This guy:

He is generally re-imagined as a folksier, Americanized version of the saint who blessed children with gifts on his feast day, December 6th. Plenty of the other Christmas songs and TV specials tie the gift-giving tradition at least slightly to the Nativity story, from The Little Drummer Boy and Nestor the Long-Eared Donkey to the line “Santa knows that we’re all God’s children, and that makes everything right” in “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” – which is a song based on the annual Hollywood Christmas Parade, not any theological work.

But not Baum. Baum does mention God a couple times in the book, but he never defines what the word means, or who that being is. In contrast, all the other Immortals are described in lavish detail, and given personality and dialogue. Claus is just Claus, a human boy rescued by a Wood Nymph. He’s not connected to Nicholas at all, and the only reason he ends up with the title Saint is that humans bestow it on him as a term of respect and love for the gifts he brings to children. It’s a title he earns after what seem like a few decades of toymaking, long before he’s granted immortality, and isn’t connected to miracles or a church hierarchy. Churches and religion are never mentioned, and Claus gives toys to all children, including children who live in “tents” in a desert, who appear to be Indigenous Americans, after a few years of traveling around what seems to be Medieval Europe. Since Ak and the Immortals have no sense of human time, neither does Claus, so we’re never told what century we’re in—only that at a certain point stovepipes replace the wide stone chimney Claus was accustomed to using on delivery night.

I wish I’d come to the book before the Rankin Bass special—Baum’s world is so weird and unique, and such a fantastical take on a Christmas story, that I think I’d rather have my own ideas of the characters in my mind rather than their (stunning) puppetry. Where else will you find a straight up Tolkien-style battle of good and evil in the middle of a Santa Claus story? I highly recommend that you add Baum’s tale to your holiday reading.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Come give her holiday reading suggestions on Twitter!